Opioid Substitution Therapy Works. India Isn’t Doing Enough

Epistemic status: Low-to-medium. This document is a shallow investigation on opioid substitution therapy (OST) access in India, focusing on buprenorphine

At Harvard Chan, We Need To Talk About Hard Things

Reposted from https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2025/10/31/narayanan-harvard-chan-school-funding-dialogue/ - Credits to The Harvard Crimson editors for supporting

We are all just animals. Why animal health is public health too

The vision of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is bold - Health, Dignity, and Justice for

Breaking rules in hospitals - some advice

I love hospitals. I understand this is odd, but I feel safe in the cloud of phenol and Dettol in

Far too much love to give - navigating school, relationships & careers

I've been accused of the unthinkable. I've been called out. A dear friend and a beautiful

Transitioning from school to work is hard! Some advice on managing the self

Cross-post from the Effective Altruism Forum: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/b3DvgFscsp2ggd9P3/transitioning-from-school-to-work-is-hard-some-advice-on

I’m in graduate school now (MPH

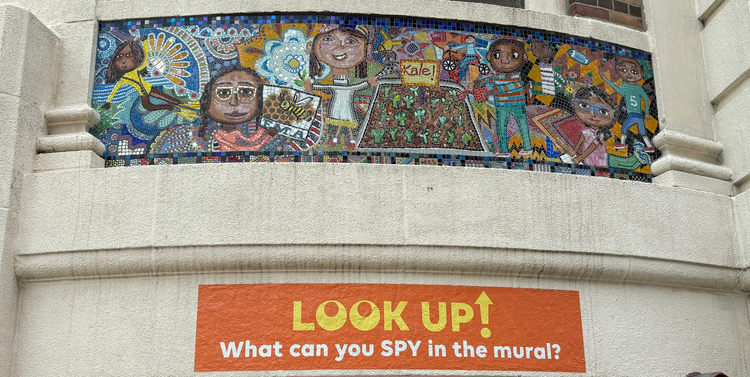

Day 4 in Boston

It's my 4th day in Boston, Massachusetts, and I'm wondering if I'll ever get

Failing to Protect India’s Children - Analysing State Capacity Deficits

With 444 million resident children, child protection forms a crucial part of India’s social development agenda. This is especially

Emotional risks in community work

Epistemic status: High - Built on experience, needs to be backed by more data

Reposted from https://globalhealthconnect.substack.com/

We're not teaching medicine well

A non-exhaustive list of reasons why medical education is currently failing in its mission to instil a rational and (therefore) people-centred mindset in practitioners.