Opioid Substitution Therapy Works. India Isn’t Doing Enough

Epistemic status: Low-to-medium. This document is a shallow investigation on opioid substitution therapy (OST) access in India, focusing on buprenorphine as the primary treatment medication. I spent approximately 15 hours reviewing academic literature, policy documents, and procurement data. I haven’t talked to any experts about this yet. I welcome comments via akshaygn@hsph.harvard.edu

Uncertainty: It seems worth flagging two major uncertainties that this shallow review does not resolve

- I am quite unsure about the tractability of regulatory reform. While the regulatory barriers are well-documented i.e. overlapping laws, unclear definitions, provider harassment, it's uncertain whether philanthropic investment could meaningfully change the legal environment.

- I am also uncertain about private sector willingness at scale. Punjab's attempts to engage private psychiatrists have faced repeated legal and operational setbacks. It's unclear if the barriers are primarily legal or reflect deeper concerns about reputational risk, liability, and operational complexity that money can't easily fix.

Executive Summary: India has 7.7 million people with opioid use disorders, but only 3%-5% of people who inject drugs, and even fewer who use opioids w/o injecting receive opioid agonist/substitution therapy (OAT/OST) despite strong clinical evidence and relatively clear government willingness. OST uses long-acting opioids like buprenorphine and methadone to stabilize patients, reduce illicit drug use, and enable HIV/HCV treatment. Buprenorphine is generally safer than methadone due to its partial-agonist ‘ceiling effect,’ and NACO’s OST program in India primarily uses buprenorphine.

Some barriers to accessing OST treatment in India:

- Stock-outs reported but scale unclear. Anecdotal reports from Manipur of "frequent non-availability" and forced dose compromises, but unknown if this is systemic or isolated. I was unable to find any information on supply chain management of buprenorphine/methadone.

- Costs/Supply do not seem to be primary constraints. Multiple Indian manufacturers (Rusan, Sun Pharma, Taj) produce buprenorphine domestically at INR 4-5/tablet in bulk procurement. Manufacturing capacity appears adequate, at first look.

- While the medicine is free in government centres, a single tablet can cost between Rs 25 and Rs 40 in private de-addiction centres. If illegally diverted to the open market, each tablet can fetch Rs 300.

- Regulatory confusion is the main barrier, Buprenorphine sits in a legal grey zone between NDPS Act and Drugs & Cosmetics Act because it is only meant to be used in "de-addiction centers only". Psychiatrists have been arrested in the past, creating provider fear.

- The private sector is absent. Despite legal pathways for prescription, private clinics face enforcement uncertainty, restricted take-home dosing, legal risk, and weak business case competing against free government programs.

- Government programs exist but aren't scaling. NACO runs 393 centers serving 44,500 people (<5% of PWID). Punjab demonstrates scale is possible (529 clinics, 10,00,000 patients), but other states haven't replicated this. Why remains unclear.

- Drug diversion concerns drive restrictive policies. Legitimate worries about tablet misuse (injection) and India's role in regional diversion contribute to daily observed dosing requirements/hardline regulation on drugs that make scaling impractical.

- Long-acting formulations are untested. Buprenorphine implants could address adherence and diversion but haven't achieved commercial uptake anywhere. Unclear why or if any LMIC has piloted them.

- The vast majority of people with opioid use disorders don't inject, yet most programs exclude them due to the government's HIV prevention/harm reduction mandate (they focus only on injecting drug users).

What should we look at?

- This looks less like typical market shaping (supply/pricing) and more like health systems strengthening and regulatory advocacy. Traditional financial tools (volume guarantees, subsidies) don't obviously apply when the constraint is regulation, provider fear and restrictive service delivery models, not manufacturing or price.

- Expanding programs beyond the current IDU (injecting drug users) only focus could dramatically increase coverage. Supporting states to create operational models for broader OST programs could be valuable, though this faces the same regulatory uncertainties.

- Delivery model innovation would ideally focus on removing the daily observed dosing requirement. Current programs mostly use plain buprenorphine, which is susceptible to diversion and injection, necessitating daily clinic visits. This creates a massive access barrier once patients return to work. Buprenorphine-naloxone formulations reduce injection risk and could enable safe take-home dosing.

- Workforce development addresses the severe shortage of trained providers. Very few teaching institutions offer OST, leaving trainee psychiatrists with minimal exposure.

- Supply chain optimization appears less critical than other barriers. However, documented stockouts in states like Manipur suggest that distribution and monitoring systems need strengthening.

- Development incentive grants could theoretically support R&D on long-acting formulations (like implants) adapted to Indian contexts, but this is an uncertain timeline.

The most relevant interventions appear to be regulatory advocacy, workforce training systems, and service delivery model innovation. These require technical assistance, convening power, and regulatory policy influence more than product-specific financing mechanisms. There may be a role for impact investment in private clinic networks if regulatory clarity improves, but that's highly contingent on policy changes.

This looks quite different from typical market shaping work on commodity products.

Some questions:

- Are the reported buprenorphine shortages in Manipur and other locations isolated incidents or symptoms of systemic procurement/distribution problems? Is this a last-mile distribution issue, a budget release timing problem, poor forecasting at state level, or something else?

- Why do we not rely on buprenorphine-naloxone combinations, if they’re similar in potency/ reduce misuse risk? Is this driven by a manufacturing/cost constraint?

- What specific efforts have been made or are currently underway to enable private psychiatrists and clinics to provide MOUD? Are there test cases in courts challenging the "de-addiction center only" interpretation? What is the Indian Psychiatric Society or other professional bodies doing to advocate for clearer regulations?

- Punjab demonstrates that large-scale outpatient OST is operationally feasible. What specifically prevents other states from replicating this model? Is it budget constraints, lack of trained staff, political will, regulatory interpretation differences, or something else? Why does NACO's program remain focused primarily on IDUs when the broader opioid-dependent population is much larger?

- Why hasn't Probuphine or similar buprenorphine implants achieved commercial uptake anywhere, including in high-income settings where regulatory barriers would presumably be lower? Is it a pricing issue, clinical acceptance, patient preference, or business model problem? Have any LMICs piloted or adopted long-acting MOUD products, and if not, why not?

Extended review:

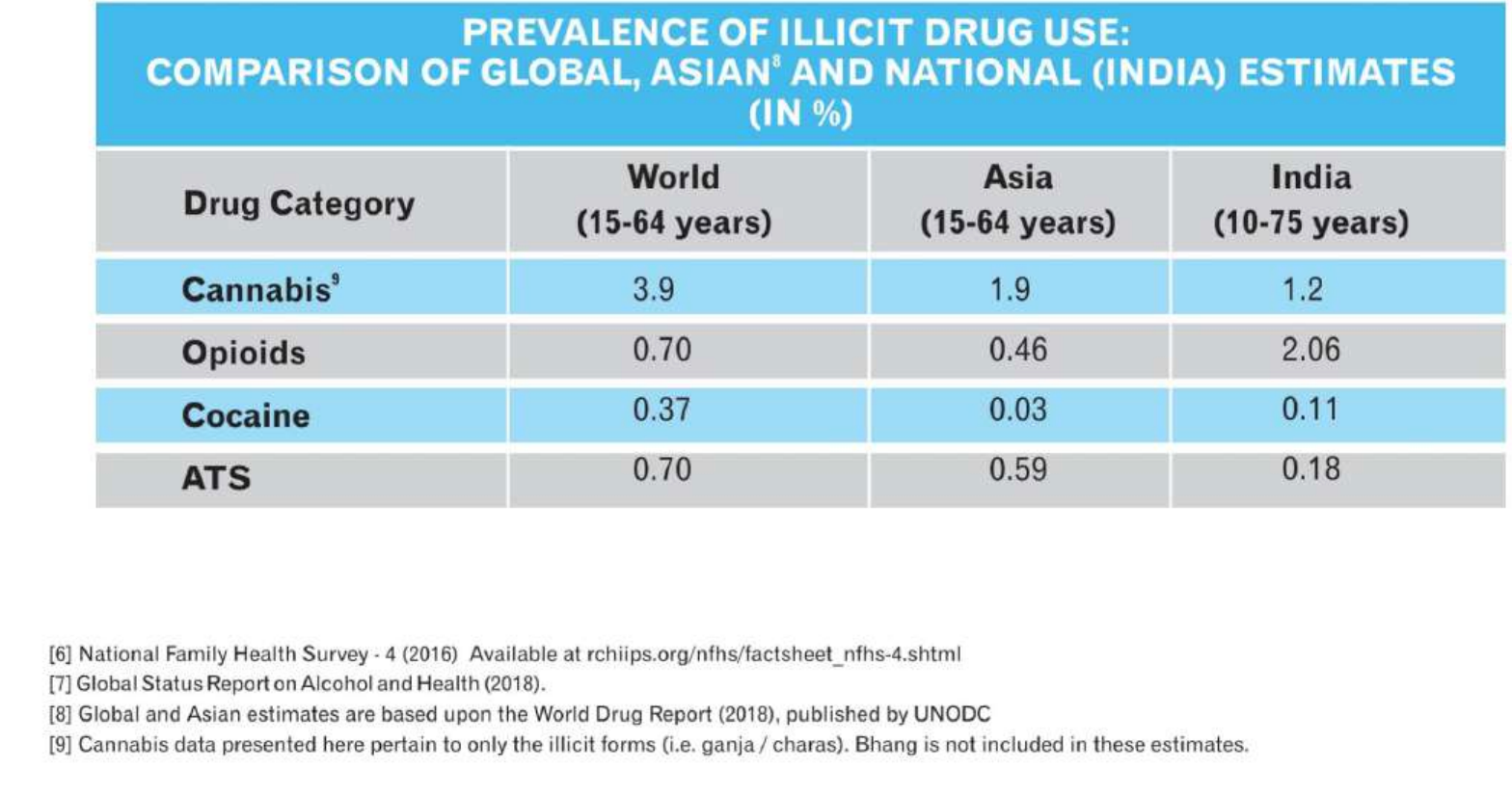

Public Health Problem: National surveys estimate that approximately 23 million Indians used opioids in the past year, with 7.7 million meeting criteria for opioid use disorders. This represents 2.1% of the Indian population, which is three times the global average. Heroin is the most commonly used opioid (1.14% of the population), followed by pharmaceutical opioids (0.96%) and opium (0.52%).

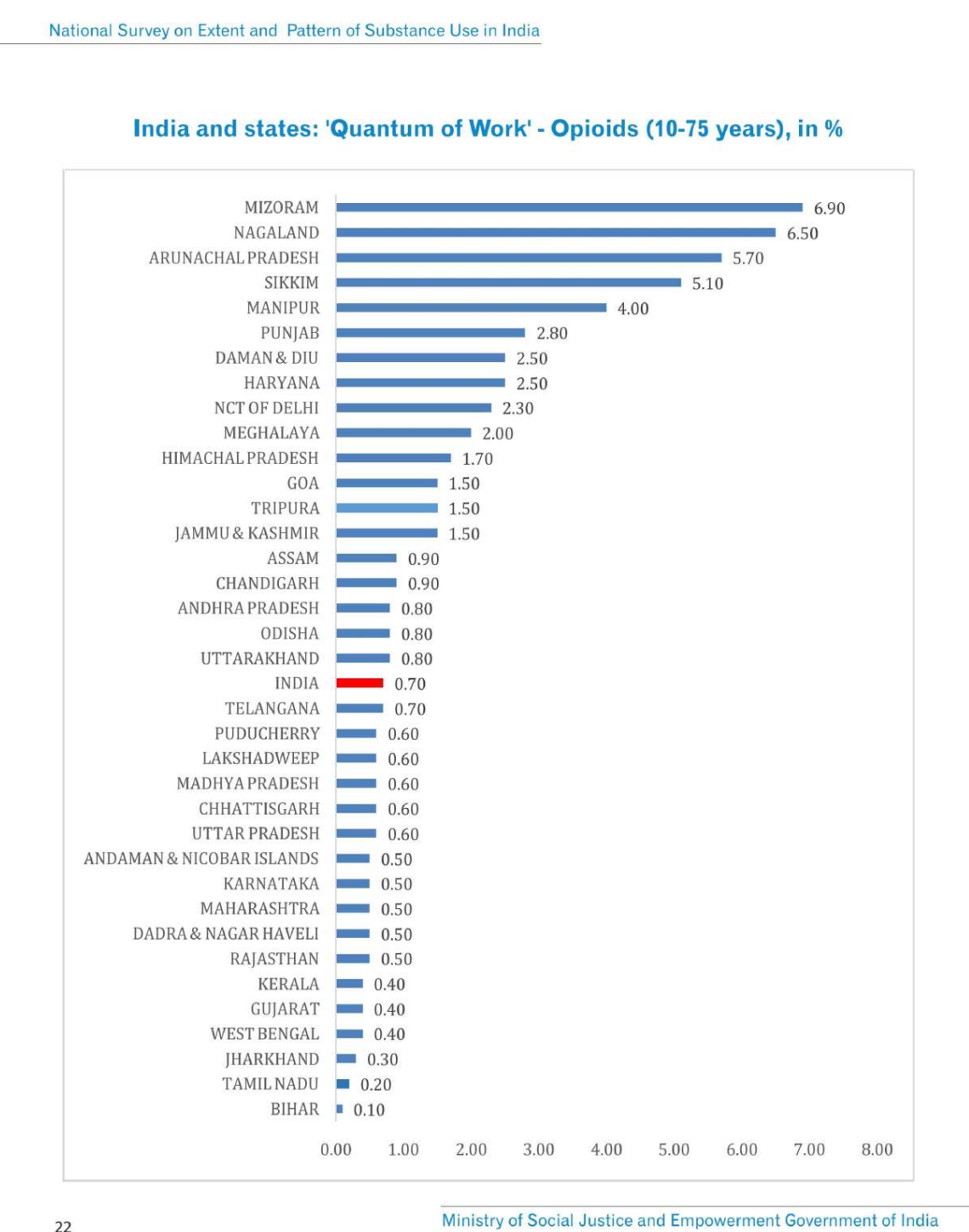

The geographic distribution is highly uneven. By absolute numbers, the highest burden falls on Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and Gujarat. However, by prevalence rates, the northeastern states of Mizoram, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, and Manipur show the highest rates of opioid use, along with Punjab, Haryana, and Delhi. In Punjab specifically, opioid dependence affects approximately 2.5% of the population, with an estimated 270,000 opioid-dependent individuals.

The injecting drug use epidemic is particularly concentrated in the northern and northeastern parts of the country. Almost all injecting drug users in India are opioid dependent, and this population faces severe health consequences. The prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs is 9.9%; the highest of any risk group in the country. Hepatitis C prevalence among this population in India is also high, with multiple sites reporting prevalence above 60% (and higher in some settings).

The treatment gap is enormous. A household survey in Punjab found that only about 15% of people with opioid dependence had "ever" received any form of medical treatment. Current OST coverage through NACO programs reaches only 3-5 per 100 people who inject drugs, which the WHO categorizes as "low coverage" (defined as less than 20 per 100). When considering the broader population of 7.7 million with opioid use disorders, current programs cover perhaps 3-4% of those in need.

What is Opioid Substitution Therapy? Opioid substitution therapy (or opioid agonist therapy) involves providing long-acting opioid medications like methadone or buprenorphine to people with opioid dependence. Rather than producing a high, these medications occupy opioid receptors at a steady level, preventing withdrawal symptoms and reducing cravings without causing euphoria.

The effectiveness of opioid substitution therapy is well-established in the international literature, and growing evidence from India supports its effectiveness in the local context. A Cochrane review concluded that buprenorphine probably keeps more people in treatment, may reduce the use of opioids, and has fewer side effects compared to other maintenance agents or psychological treatment alone. It also showed that methadone may keep more people in treatment than buprenorphine. The evidence shows that treatment outcomes are better with adequate dosing; usually 60mg of methadone or 8-16mg of buprenorphine daily.

OST provides multiple public health benefits beyond individual treatment outcomes. It reduces mortality in people who inject drugs and improves their quality of life. The intervention increases hepatitis C testing rates and treatment uptake with direct-acting antivirals. Similarly, it boosts antiretroviral therapy enrollment, adherence, and viral suppression in HIV-positive people who inject drugs.

A study of integrated care models that combine pharmacological treatment with psychosocial interventions found that patients receiving integrated care had higher rates of treatment retention and abstinence at 12 months compared to those receiving standard care.

Buprenorphine vs Methadone. A comparison of methadone and buprenorphine in Indian inpatient settings found both medications effective for acute opioid withdrawal management. Indian guidelines note buprenorphine can be initiated in outpatient or inpatient settings; as a partial agonist with a ceiling effect, it has lower respiratory-depression/overdose risk than methadone and lower abuse liability than full agonists, and many studies find less cognitive impairment on buprenorphine than methadone; supporting efforts to expand access where feasible.

- In India specifically, buprenorphine remains the primary agent for opioid withdrawal management given its earlier regulatory approval and more extensive domestic evidence base. Methadone was only approved by regulatory authorities in 2010 and is available in select tertiary centers, with acknowledged gaps in Indian clinical experience.

- However, it’s important to note that flexible dose methadone maintenance (UK£14,000; US$23,100; Indian Rupees 1,030,400) performs somewhat better in terms of quality-adjusted life years than buprenorphine (UK£27,000; US$44,550; Indian Rupees 1,987,200) when both are compared to no drug therapy for heroin users.

- Buprenorphine is probably the safer agent. However, its relative advantage over methadone in these safety domains is somewhat tempered by the emerging evidence of problematic diversion and the risks associated with the intravenous use of crushed tablets.

- Buprenorphine-naloxone is basically buprenorphine with a built-in deterrent. If you take it under the tongue as intended, it works normally, but if someone tries to inject it, the naloxone can trigger withdrawal and blunt the high, which is why programs use it to reduce injection misuse and make take-home dosing safer.

Current infrastructure for OST: The existing service delivery landscape is fragmented across multiple government programs.

- Centers and clinics under the Drug De-Addiction Program (DDAP) of India: DDAP provides services primarily through de-addiction centers (DACs) and drug treatment clinics (DTCs). A total of 27 DTCs were functional across India as of 2019.

- Addiction Treatment Facility (ATFs) under the National Action Plan for Drug Demand Reduction 2018, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE): Similar to DTCs, other centers, called ATFs, for out-patient treatment, including OAT, were initiated under the MoSJE. As of February 2023, 25 such centers were functional, with a plan to scale up such centers to 125 districts in India. (no updates on this plan)

- Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) centers under the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO): NACO provides OST to PWID through OST centers run by three models: GO-NGO model, NGO model, and Satellite clinics. Apart from this, they also provide NSP through targeted intervention sites. As per the Status of National AIDS Response 2023, there are around 393 OST centers across India including 200 in public health settings, 46 in NGO facilities, and 147 satellite centers. Under this program, around 44,553 PWIDs are currently receiving OST. As per NACO estimation, 23% of the active PWID population is receiving OST during this period.

- Outpatient Opioid Assisted Treatment (OOAT) clinics under the Punjab Government: OOAT clinics were started in 2017 in both government and private settings in the state of Punjab (National Health Mission, Punjab, 2017). In 2022, OOAT clinics were initiated in PHCs, CHCs, and prisons. As of one estimate, there are now around 529 OOAT centers in Punjab, and around 10 lakh patients seek treatment daily at these centers.

- NACO's program focuses primarily on injecting drug users, which means the larger population of opioid-dependent people who don't inject remains largely unserved.

Barriers to OST access

Manufacturing and pricing: This doesn't appear to be a classic supply constraint problem.

- Multiple Indian manufacturers produce buprenorphine domestically. Rusan Pharma markets Addnok (buprenorphine) and Addnok-N (buprenorphine-naloxone); so do Sun Pharmaceutica, Taj Pharma and Parb Pharmaceuticals

- Bulk procurement costs run as low as INR 4-5 per 2mg tablet, which works out to roughly INR 20-25 per day for treatment. In private retail settings, the same tablets sell for INR 30-40 each, meaning an 8mg daily dose would cost INR 120-160 per day or INR 3,600-4,800 monthly.

- Here’s one tender; here’s another tender; and another piece that talks about the low cost of purchase.

So the manufacturers exist, the API production is there, and the pricing in government procurement appears quite affordable. Methadone costs are nearly equal to buprenorphine currently and could fall further with more suppliers entering the market. This suggests the typical market shaping interventions around supplier entry, volume guarantees, or price negotiations may not be the primary levers here.

Coverage & stockouts: While manufacturing capacity appears adequate, there's scattered evidence of actual supply chain failures at the service delivery level.

- A 2022 case registered by the Manipur Human Rights Commission noted "frequent non-availability" and "denial" of OST medicines at specific health centers (Kakching CHC, Ukhrul District Hospital, Senapati District Hospital).

- In March 2021, The Sangai Express reported that Ukhrul OST sites needed approximately 50,000 buprenorphine tablets monthly but had received "very less" since November 2020, forcing dose compromises and raising relapse risk.

These are anecdotal reports from news sources, not systematic data. It's unclear whether these represent isolated procurement failures in specific states, or whether there are underlying supply chain inefficiencies despite adequate manufacturing.

Funding landscape: Total OST funding in India is difficult to estimate precisely but appears quite limited relative to the scale of need. The funding landscape is dominated by government programs. I couldn’t find any evidence of international philanthropic engagement, barring work with wraparound services (awareness, counselling etc). There are NGO implementation partners for NACO programs, but I haven't identified substantial independent philanthropic investment in addiction treatment infrastructure or policy reform. This is in stark contrast to other health areas like tuberculosis, HIV, or malaria, which receive significant international donor attention.

NACO operates as the primary funder for approximately 393 OST centers, but their exact budget allocation for OST specifically is unclear. It's embedded within broader HIV prevention spending. The Drug De-Addiction Programme faces chronic underfunding.

- Reviews of DDAP note (qualitatively) that challenges include no regular funding for most centers, low priority given to de-addiction services by state health departments, inadequate staffing, irregular medicine supply, and lack of support staff such as nurses, social workers, and counselors.

- For example, while it provided one-time setup grants for 122 de-addiction centers, only the 43 centers in the Northeast receive recurring operational grants of INR 2 lakh per year (approximately $2,400).

The regulatory environment effectively blocks greater private sector participation at scale, and there's no evidence of corporate social responsibility initiatives or pharmaceutical company access programs addressing this gap.

Regulation: The real barrier appears to be regulatory confusion that creates provider fear/genuine legal bottlenecks for expanding access to OST services.

Buprenorphine sits in what is described as a ‘legal grey zone’. It's regulated under both the NDPS Act (as a psychotropic substance) and the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (as a Schedule H1 drug), and these frameworks don't align neatly. The Drug Controller General initially approved buprenorphine "for supply to de-addiction centres only" through internal communications, but this term isn't actually defined in either the NDPS Act or the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. So different officials interpret it differently.

- Psychiatrists have been arrested in Punjab over buprenorphine stocking and dispensing disputes. Many doctors simply avoid stocking or dispensing buprenorphine even when there's demand, because the penalties under NDPS can be severe and the legal interpretation varies by enforcement officer.

- Buprenorphine did not make it onto that Essential Narcotic Drugs list, which is paradoxical compared to international standard practice where methadone prescription is highly regulated and buprenorphine allowed for outpatient use.

- Instead, India's regulatory structure has made methadone somewhat more accessible through the Recognised Medical Institution pathway, though this still requires specific permissions, extensive recordkeeping, and direct administration requirements that limit take-home doses.

- Some states permit outpatient buprenorphine prescription while others prohibit it, and the law is somewhat silent on whether OST must have inpatient facilities. The 2015 NDPS rule clarification says "for use in his practice" means direct administration to patients under care, and explicitly states that "home care treatment shall not be provided for treatment of opioid dependence." This creates a structural barrier to take-home dosing models.

- A recent prospective study of outpatient buprenorphine-assisted withdrawal management in Delhi found 67% retention at 12 weeks with over 80% abstinent among those retained. This compares favorably to inpatient studies despite the challenges of outpatient treatment.

Insufficient delivery channels: Regulatory constraints described above severely limit how OST can be delivered. NACO's OST program is "focused heavily upon injecting drug users" despite many opioid-dependent people not injecting, leaving a large unmet need. This is because OST coming under NACO makes it a focus on AIDS prevention. A large proportion of people with substance use disorders can be provided help in the outpatient settings.

- Daily observed dosing requirements (to prevent diversion) create a structural barrier to scale because they make treatment "hard to stick with and hard to scale." Patients can't maintain jobs if they need to show up daily, clinics face high workload with low margins, and there's legal and reputational risk

- The introduction of buprenorphine-naloxone combination tablets was specifically designed to address this tension. The naloxone component makes injection less attractive (it blocks the opioid effect if injected while having minimal effect when taken sublingually as directed), which should enable safe take-home dosing for stabilized patients. Some programs have successfully implemented graduated take-home protocols, allowing patients to transition to weekly pickups after a stabilization period. However, NACO programs have primarily continued using plain buprenorphine.

- Private clinics are largely not participating, despite apparent demand and the existence of legal pathways. A registered medical practitioner can prescribe buprenorphine under Schedule H1 requirements with proper recordkeeping. If a clinic wants to stock and dispense (rather than just write prescriptions), it needs to comply with Schedule H1 dispensing rules and applicable state regulations. For methadone, it's more complex. Private facilities would need Recognised Medical Institution status under the NDPS framework, with specific permissions and extensive recordkeeping routed through the State Drug Controller.

- The practical reality is that even where legal pathways exist, private providers face uncertainty about enforcement, fear of prosecution, low-margins, reputational concerns, limited take-home dose flexibility that makes care delivery impractical, and competition from free or subsidized government programs that undercut private pricing.

- Unsure if the Indian Psychiatric Society or other professional associations are advocating for regulatory clarity, or what legal cases might be in progress to challenge the ambiguities.

Diversion concerns: Part of the regulatory anxiety stems from legitimate concerns about diversion and abuse. India is believed to account for significant large-scale diversion within South Asia and beyond through poor regulation of illicit opioid production and pharmacies. There's documented evidence of buprenorphine tablets being injected rather than used sublingually, which both misses the therapeutic intent and creates health risks.

Long-acting formulations - R&D Gaps: Long-acting formulations could theoretically address multiple problems at once. Improving adherence, reducing diversion risk, and reducing accidental exposure compared to pills that need to be taken home or dispensed daily. A 2016 JAMA trial tested Probuphine, a six-month buprenorphine implant, against continued daily sublingual buprenorphine in patients who were already stable on treatment. The implant group met non-inferiority targets with very high response rates and similar withdrawal/craving scores to the sublingual group.

However, Indian reviewers raised important caveats about generalizability.

- The study enrolled a highly selected "best prognosis" group, basically people who were already long-term stable and abstinent, so success rates may be inflated and may apply to only a small fraction of real-world OST patients.

- Some implant patients still needed supplemental sublingual dosing, suggesting episodic craving that monthly measures didn't capture.

- What's unclear is why Probuphine or similar products haven't taken off commercially anywhere. If the product exists and addresses key concerns around adherence and diversion, what prevents commercialization? Is it a pricing issue, lack of clinical acceptance, patient preference for pills, manufacturing complexity, or something else? There's no information available about whether any LMICs have piloted or adopted long-acting MOUD products, and if not, what the specific barriers have been.

Workforce Capacity and Training: The shortage of trained providers represents a bottleneck to scale-up.

- Very few teaching institutes in India offer OST as part of their training curriculum. This means that there are hardly any opportunities for trainee psychiatrists to gain knowledge and skills in providing OST during their residency.

- In some qualitative studies of stigma in substance-use treatment, I’ve seen reports of some members of the psychiatric fraternity displaying an attitude of looking at OST as "just substituting one addiction for another," despite the strong evidence base supporting its effectiveness.

- There's also a misconception that only psychiatrists can deliver OST, when international evidence and limited Indian experience demonstrates that nonspecialist physicians can be effectively trained to deliver this treatment. The shortage becomes even more severe when you consider that medical officers (MBBS graduates) typically have no exposure to the treatment of addictive disorders during their training.

- Task-shifting to trained medical officers is technically feasible - the clinical protocols are standardizable and don't require specialist psychiatric expertise for stable patients. But, this requires certification and supervision structures that don't currently exist at scale.